Welcome back to my series of posts on my current MSci project: The Completeness of the Fossil Record of Pterosaurs. It’s been a while!

For those of you who’ve seen my last proper post, you’ll have noticed my visit to the NHM, which sort of marked the start of this MSci malark, was while a while ago now. In fact, we’re now quite near the end; as it’s now nearly January the project is due in in about 2 weeks! Which begs the question: what the hell have I been doing with my time since then?

Well, apart from catching up on four seasons of Parks and Recreation, I have actually made some significant progress on my MSci project. I know, it surprises me as much as it probably does you. So my aim of the next few posts is to bring you up to speed with my progress on the different parts of my project, starting with the literature review and database assembly.

First I have to cast your collective minds back to the beginning of October. I started my MSci project pretty much as soon as I’d finished that seminal right of passage for any geologist, the independent mapping project (*shudder*). My first task was to produce a literature review on the material relevant to my project. This is pretty much what it says on the tin; it’s a report into the previous work, and in particular authors viewpoints, on the topic that you’ve chosen to work on. Luckily, although pterosaurs have been studied far more than many other groups, previous research for the kind of work that I’m doing is pretty limited. Only a few authors have really thought about pterosaur diversity and disparity in relation to fossil bias, and only one paper has briefly mentioned completeness in passing, in a much less refined way than the methods I’m using. What’s nice about all this is that it provides a pretty good groundwork for me without encroaching on my project – similar stuff on diversity is good, as I can use this as a basis to build up my work from.

Doing the literature review was good in many ways – it forced me to be acquainted with the big names in the field, as well as giving me a good grasp of what’s going on, so I don’t end up covering things other people have already looked at. Overall there’s two main camps when it comes to completeness and diversity within the fossil record. There’s those who think that the methods we’re using are adequate, and are able to remove at least some of the bias associated with the fossil record, leaving a partially ‘true’ record of diversity through time. There’s also those who think the exact opposite, and that using various proxies to remove bias is ineffective. This has pretty big implications for the way we look at the fossil record in general, so it’s important to sort it out, and it’s nice to know that my work can go at least a little bit of the way in trying to come to a sensible conclusion. If people are interested, I’ll my literature review up on after my project is handed in; it’s possibly a bit heavy going and it’s a little bit naff, but it should hopefully give you a good grasp of the general field!

After the literature review came the bulk of the work – compiling the database. Now to do any kind of palaeontological work on a group like the pterosaur, with approximately 160 species, you need to collect all your data in one place. In this case, I was initially finding the completeness for each species of pterosaur; I gathered additional info for species later to test out different ideas, but I’ll chat more about that in a bit.

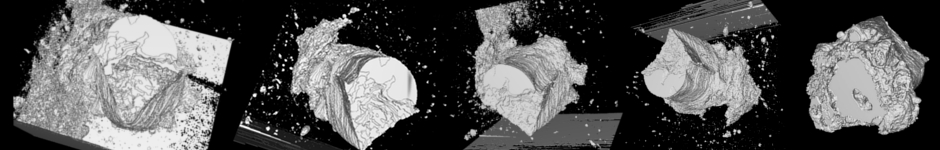

Now I was lucky enough to be given somewhat of a headstart by Brian Andres, who is currently reworking a complete phylogeny of pterosaurs . He was kind enough to give me an old but large database of pterosaur species which in total showed about 100 pterosaur species and listed 183 distinct characters – a very good start I’m sure you can agree. It was also made easier by the fact the species were already coded. As I mentioned in my last post, completeness using the CCM method is based around how many characters can potentially be coded in a species as a percentage of the total characters – so if you’ve got enough information in the bones of a species to code 40 characters out of a possible 100, that’d have a completeness of 40%. As these species were already coded, this meant all I had to do for the initial 100 was to go along each species and count how many characters had been coded, and give that a percentage value out of 183. Not too hard! This took a pretty short time to do, but was pretty monotonous. Such is science!

The harder bit came next – filling in the missing species. This proved a bit of a problem because the way pterosaurs have been named is, frankly, awful. To understand this, you firstly need a bit of background. The first pterosaurs were discovered in the 1800’s, and were part of the great revolution of palaeontology. At this time, palaeontology was a bit of a gentleman’s thing, with rich noblemen taking it up in their spare time. As such, the interests and focuses of the science were also different – much more emphasis was placed on finding and naming species than looking at taxonomic relationships or past environment, and therefore it became somewhat of a race between people to see who could name the most species. This meant that new species were often assigned based on a single piece of bone or fragmentary remains just to add to a tally of total names. Pterosaurs suffered pretty badly with this due to remains often being fragmented due to their fragile nature, and many species ended up being named incorrectly. Pterosaurs have been revised pretty heavily since, but there’s still a lot of old species names that linger around despite not actually existing as such. So as you can imagine, it took a while to get the additional names together. I mostly used something called the Paleobiology Database (PBDB for short) to get these final names. This is the most extensive database of palaeontological data online, aiming to put together all the information possible on fossils found around the world. Luckily, it’s pretty complete for pterosaurs! Jon Tennant of the excellent Green Tea and Velociraptors has written a nice introduction to it here that explains it all in much better detail than I’d be able to if you’re interested in finding out more.

PBDB logo. Source

After doing this, my task was to revise the list for any Jr. Synonyms or Nomen Dubium. Jr. Synonyms are where a species has accidentally been named twice for some reason. This could be due to revision from one genera to another, or just purely accidental. Having two species instead of one would distort the data, so these were pretty crucial to find. Nomen Dubium is latin for ‘doubtful name’, and exists where the fossil that was used to name the species has since been looked at and found to not contain enough information to adequately assign a species. Once I’d rooted out all the errors, I was left with a list of 160 species in total.

However, the story doesn’t quuuiite end there; since doing this I’ve been in contact with Brian, and he’s given me a revised list that’s fairly close to my own, but has quite a few more species. This is because he’s been able to look at specimens in museums, and use his extensive knowledge of pterosaurs to establish whether of not he thinks they belong to the same species or not. This might call for a reworking of my data at some point, but with the deadline looming this may well have to wait a bit!

Next time I’ll be talking about the rest of the data that I assembled and the methods I used to generate my statistics and graphs. Stay tuned!

Today’s post title comes from this great song.