It’s 8:45pm. I’m sat on a crowded megabus to Bristol for a course in Quantitative Palaeobiology and I’m sat opposite a girl who looks a lot like Aleks from Los Campesinos (Note: I later found out it definitely wasn’t, which was pretty upsetting). I’d call that the perfect time to give you all an update into my first few months of my PhD.

When I left you last I had returned out of the blue to let you all know I was starting a PhD at my old haunt of Imperial. But now it’s 2 months or so later, and on the first of January I have my first major milestone; to submit something called a Three Month Report. One of the big bonuses about doing a PhD is that there are no formal written exams. This is, unsurprisingly to those who know me, a massive relief. However, there are steps which you have to complete along the way, and the Three Month Report is the first of these. Essentially it’s a short plan, roughly 2 or 3 pages, that details the outline for your project and what you plan to accomplish during your time. Now I realise that in my last post I fell short of actually talking about what my project is. So what better time to run you through the work I’m hoping to tackle in the next 3 or so years?

Now one of the original aims of this blog was to make sure I communicated my work so it was possible that anyone could understand what I was hoping to accomplish. In keeping with this I’m going to work through my project in 4 simple steps. For this post, I’m going to cover the first (and most important) two: what’s the project about, and why should we care?

What is my project about?

Let’s start with the title and go from there. Although it’s bound to change some point in the future, my current project title is this:

“Evaluating preservation and environmental impacts on biodiversity in epicontinental seas”

In a nutshell, I’m attempting to look at how biodiversity was influenced by environmental change and how it is preserved in the fossil record in epicontinental seas. Epicontinental seas were vast, ancient oceans which covered the continents in the past. They were warm, shallow environments which were teeming with life, and therefore are excellent resources for finding and studying marine fossils around the world today. My project takes place in two steps; I’m aiming to systematically remove bias (my favourite word!) from the record of epicontinental seas so that we can see what useful data is left, and then secondly attempt to carry out some neat modeling approaches to see how organisms within these oceans were effected under different conditions. I’m looking particularly at the Western Interior Seaway for this project. This was an ancient sea which covered North America from about 120 to 60 million years ago during the Cretaceous period, when global sea level were much higher than today.

It stretched all the way from Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico, effectively splitting the continent in half; the effect of this can actually be seen in the evolutionary history of many species, including tyrannosaurs. I’ve chosen to look in particular at this seaway for several reasons:

- It’s extremely recent. One of the fundamental guides of geology in general is the law of uniformitarianism; “The Present is the Key to the Past”. This has been used for centuries to discern events in the geological and fossil record. However it has its limited; the further you go back, the less accurate it is. Therefore if you’re trying to evaluate biodivveristy and ecosystem patterns in the past, you’ll get the most accurate results in recent history. The Western Interior Seaway is perfect for this as in terms of geological time, the Cretaceous is right on our doorstep. I’m sure you’ve all heard before about the clock of history – the idea that if you condensed all of geological time into just 24 hours then humans would appear at about 75 second before midnight. The cretaceous falls within the last half hour, which by all accounts is pretty good!

The Clock of Time: All of history condensed into a simple 24 hour clock. Source

- It’s well exposed. It’s all well and good picking somewhere specific for fieldwork, but if you can’t access it, because it’s poorly exposed or not exposed at all, then it’s not going to be of much good. Luckily there is an excellent rock record in the US for this time period, which is idea for fieldwork. This means any predictions I make from models are testable, which in turn produces better science!

- Lots of data. There are an absolute boat load of fossils which have been discovered in North America. A quick search of the Fossilworks database chucks up ~8500 collections which contain some kind of fossiliferous material from the Cretaceous. The more data points you have, the more you can be sure of your results (in theory!), so it’s nice to know that it’s an area rich in fossiliferous remains.

Hopefully that’s provided a short into to what my project’s about. But more importantly…

Dodger asks the important questions. source

Why should we care?

Ask people you know about what palaeontology is and you’re guaranteed to be given a quizzical look and one of two responses: either “Is that, like, bones?” or “Like what Ross from Friends does?”. Now whilst I don’t mind this in the slightest (David Schwimmer is a babe after all), it actually deflects from what is the real crux of palaeontology: using our knowledge of life in the past to give us a prediction about life in the future. There are very few sciences that have access to something like the fossil record; it is a wealth of information in both time and space, allowing for us to unravel events over timescales much longer than our own short lifespans. This is what really interests me in palaeontology and I’m sure I’ll talk about it more in the future, as it’s a point that needs to be driven home much more. But for now, it provides the main reasons which explain why I feel this project is important.

The Phanerozoic (From about 542 million years ago to now) is our most useful record of biodiversity crisis and climate change and it just so happens that epicontinental seas provide most of our record for this period. In fact, epicontinental seas account for a huge amount of our marine fossil record. As none exist today, that raises the question how well can we understand these environments and specifically their biodiversity and ecology if we have no living comparison? This is a huge bias which needs to be better understood, and is definitely worth investigating.

But the really interesting thing is when we start to apply the knowledge we learn from this to the modern day environment. If we want to be able to understand how the marine environment of today is going to react to climate issues, we first have to understand if and how it behaves differently from these shallow land-covering seas of the past. If we can observe the effects of these environments on extinct species over long periods of time, we can potentially identify the key factors involved with the rates of extinction and origination of species, and compare these to simulations for the present. If this work provides a close enough analogue for open ocean conditions of the present, then this opens the door for a whole range of studies into the effects of climate change, pressure on ecosystems in changing environments, and other aspects of conversation ecology.

Obviously this is far flung stuff; it’s very likely that the focus of my work will shift many times over, and some of the ideas I’d like to work on might rely on data which is too incomplete or may simply prove to be too complex to fully understand or realize on such timescales. But these are ideas, and they’re a good place to start.

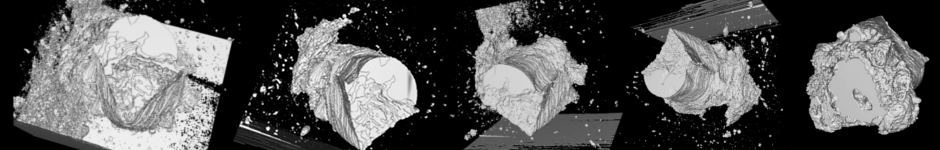

An example of some of the creatures found in the Western Interior Seaway. Source

I’ll be back soon to fill in the final sections of the report; how will my project be accomplished and what I’ve been doing so far. Cheers for reading!

Todays’ post title comes from this great song.

Hi Chris, good to find out more about your PhD. I love the idea of the Western Interior Seaway going through the middle of the US. Thanks for tweeting my blog. The faultline posts were my first foray into geology (but hopefully not my last), as you could probably tell 🙂

LikeLike